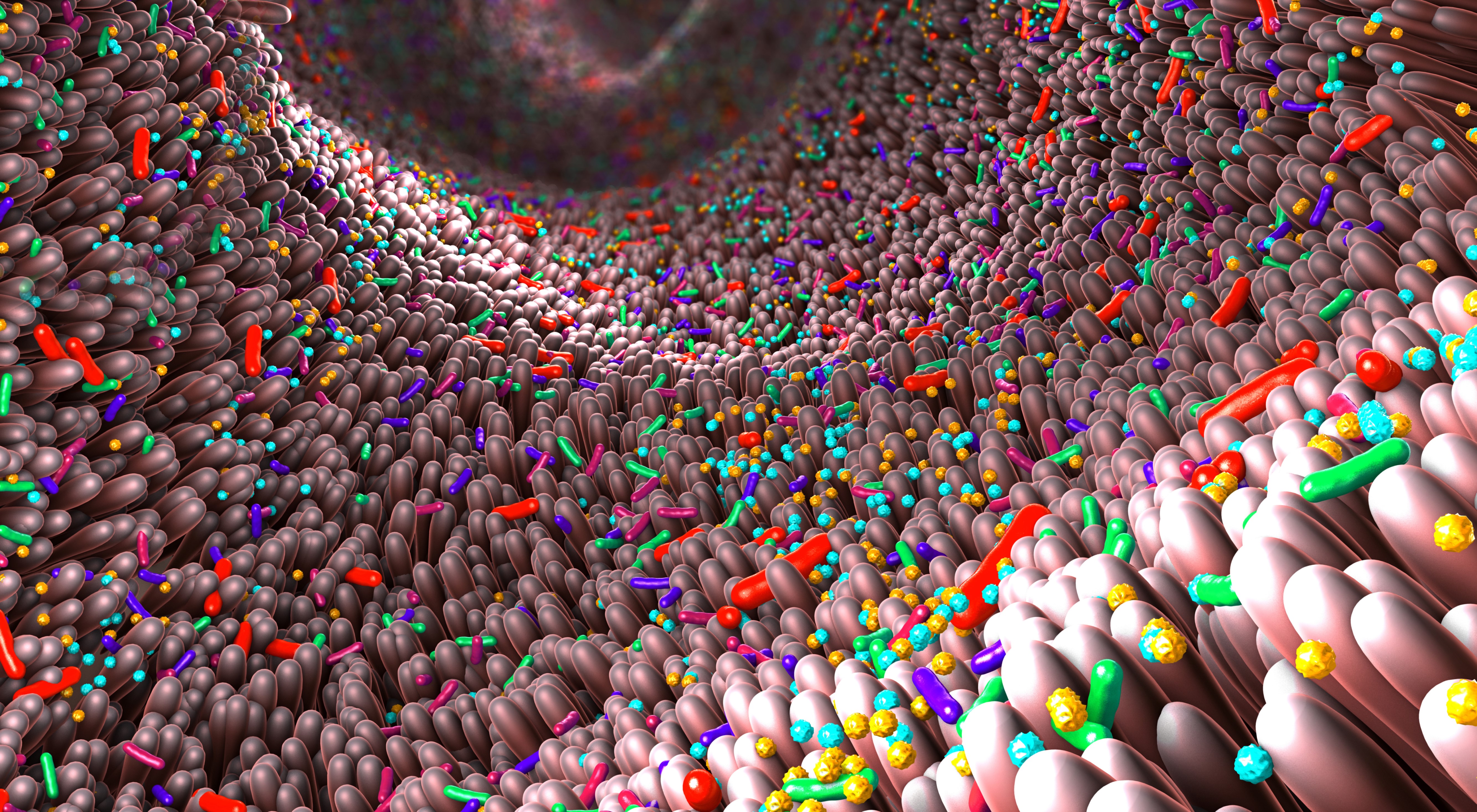

We get healthy dietary fibres from consuming fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. But why are the fibres so good for us? A team of researchers has discovered that dietary fibres play a crucial role in determining the balance between the production of healthy and harmful substances by influencing the behaviour of bacteria in the colon.

Dietary fibres benefit our health, and scientists from DTU National Food Institute and the Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports at the University of Copenhagen have now uncovered an essential part of why this is the case. Different types of bacteria inside our colon compete to utilize an essential amino acid called tryptophan. This competition may lead to either good or bad outcomes for our health. The research, published in the scientific journal Nature Microbiology, reveals that when we eat many dietary fibres, gut bacteria help turn tryptophan into healthy substances. But if we don’t eat enough fibres, tryptophan can be converted into harmful compounds by our gut bacteria.

“These results emphasize that our dietary habits significantly influence the behaviour of gut bacteria, creating a delicate balance between health-promoting and disease-associated activities. In the long term, the results can help us design dietary programs that prevent a range of diseases,” says a professor at DTU National Food Institute, Tine Rask Licht.

Dietary fibres determine the battle over tryptophan.

Researchers have long known that dietary fibres are directly converted into healthy short-chain fatty acids by gut bacteria in the colon. However, the new study surprisingly shows that dietary fibres also contribute to good health by preventing the conversion of the amino acid tryptophan into harmful substances and promoting its conversion into beneficial substances in the colon.

“The gut bacterium E. coli can turn tryptophan into a harmful compound called indole, which is associated with the progression of chronic kidney disease. But another gut bacterium, C. sporogenes, turns tryptophan into healthy substances associated with protection against inflammatory bowel diseases, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and neurological diseases,” says Anurag Kumar Sinha, a DTU National Food Institute researcher.

Through multiple experiments in bacterial cultures and mice, the researchers demonstrated that fibre-degrading gut bacteria, such as B. thetaiotaomicron, regulate the indole-forming activity of E. coli.

“B. thetaiotaomicron assists by breaking down fibres into simple sugars, which E. coli prefers over tryptophan for growth. The sugar components from the fibres prevent E. coli from turning tryptophan into indole, thereby allowing C. sporogenes to utilize tryptophan to produce healthy compounds,” says Anurag Kumar Sinha.

Understanding the behaviour of gut bacteria

It is well-known that dietary fibres can alter the composition and quantities of bacteria in our gut microbiome. However, looking merely at the composition and abundance of gut microbial species will not tell us much about their impact on our health.

“The gut microbiome research field has had a strong focus on assessing effects, e.g. of diet on the quantity of potentially good or bad gut bacteria, but often neglect that diet can regulate the gut bacteria’s activity without necessarily making major changes in the number of bacterial species in the colon,” says an associate professor at DTU National Food Institute, Martin Frederik Laursen.

So, dietary fibres not only help modify the types of bacteria in the gut, leading to a healthier composition, but they also influence the behaviour of gut bacteria in ways that promote health.

“As a research community we need to change focus from viewing gut bacteria and their abundances strictly as either good or bad – to understand instead how we make our gut bacteria behave good or bad.” says Martin Frederik Laursen.

This understanding can help scientists develop better dietary recommendations that keep our gut healthy and prevent diseases.

Facts

- Essential amino acids, such as tryptophan, must be obtained through the diet since the body cannot synthesize them.

- Protein-rich foods serve as sources of tryptophan. Examples include chicken, turkey, salmon, tuna, eggs, milk, cheese, yogurt, legumes, nuts, and seeds.

- Dietary fibers are present in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

As with anything you read on the internet, this article should not be construed as medical advice; please talk to your doctor or primary care provider before changing your wellness routine. WHN does not agree or disagree with any of the materials posted. This article is not intended to provide a medical diagnosis, recommendation, treatment, or endorsement. Additionally, it is not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, club, organization, company, individual, or anyone or anything. These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration.

Content may be edited for style and length.

References/Sources/Materials provided by:

This article was written by Lene Hundborg Koss at the Technical University of Denmark