The CAR T-cell therapy used in the study is still experimental and differs from others currently approved to treat cancer. In large part, that’s because the engineered immune system cells at the core of the treatment were packaged in a biodegradable material called a hydrogel and then injected directly into tumors.

In the mouse experiments, the treatment not only destroyed advanced tumors, but also appeared to spare the mice from losing their vision—a significant concern for those diagnosed with retinoblastoma. The results of the study were published October 12 in Nature Cancer.

To date, the CAR T-cell therapies that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration all are body-wide, or systemic, treatments—that is, they are given to patients as intravenous infusions. But, for a cancer like retinoblastoma that forms in the eye, injecting the engineered immune cells packaged in hydrogels directly into tumors could be a more effective alternative, said one of the study’s lead investigators, Barbara Savoldo, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“This was a great opportunity…to see if we could synergize these [two] technologies,” Dr. Savoldo said. The approach of directly injecting CAR T-cells into tumours rather than using intravenous infusion “may also open up possibilities for treating other tumors,” she added.

Retinoblastoma Treatment: Effective and Evolving

As its name implies, retinoblastoma develops in the retina, in the back of the eye. In the United States, only a few hundred children, mostly kids younger than 2 years old, are diagnosed with this cancer every year. About 40% of these cancers are due to an inherited genetic mutation in a gene called RB1. In most patients with the inherited form of retinoblastoma, the cancer affects both eyes.

Treatment is selected based on a variety of factors and can include therapies that kill tumors with extreme heat or cold, as well as chemotherapy and radiation, explained Efren Gonzalez, M.D., director of ocular oncology at Boston Children’s Hospital, who was not involved in the study.

Surgery to remove the affected eye or eyes, known as enucleation, used to be common, Dr. Gonzalez said. But treatment advances over the past 20 years have diminished the need for surgery.

One such advance is a treatment pioneered at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) more than a decade ago, called ophthalmic artery chemosurgery. The approach allows chemotherapy to be delivered directly to the eyes via the ophthalmic artery, and a report from MSKCC shows that it can dramatically reduce the number of children who have to undergo enucleation.

Even so, the current treatments can have serious side effects in some children, including the development of a different (or second) cancer later in life.

In addition, retinoblastoma can return after initially successful treatment, and effective treatment options—particularly those that can spare the child’s vision—are limited at that point. For these children, initially, at least, an immune-based treatment like CAR T-cell therapy could provide a better option than existing treatments, Dr. Savoldo said.

A CAR T-Cell Therapy with a Few Enhancements

The inspiration for testing this particular CAR T-cell therapy against retinoblastoma came from some of the same UNC researchers’ studies of it in neuroblastoma, another childhood cancer that shares some of the same molecular features with retinoblastoma. Based on success in mouse models of neuroblastoma, an experimental CAR T-cell therapy similar to the one used in the retinoblastoma study is currently being tested in a clinical trial for children with neuroblastoma.

The CAR T-cell therapy used in the neuroblastoma and retinoblastoma studies is directed to cancer cells that produce a molecule on their surface called GD2.

GD2 is only produced in a limited fashion in normal cells and not at all on normal retina cells, explained Anandani Nellan, M.D., and Terry Fry, M.D., of Children’s Hospital Colorado, in an accompanying commentary in Nature Cancer. And GD2 has already been shown to be a good target for immune-based treatments, Drs. Nellan and Fry added, making it “an attractive candidate” for immunotherapy for retinoblastoma.

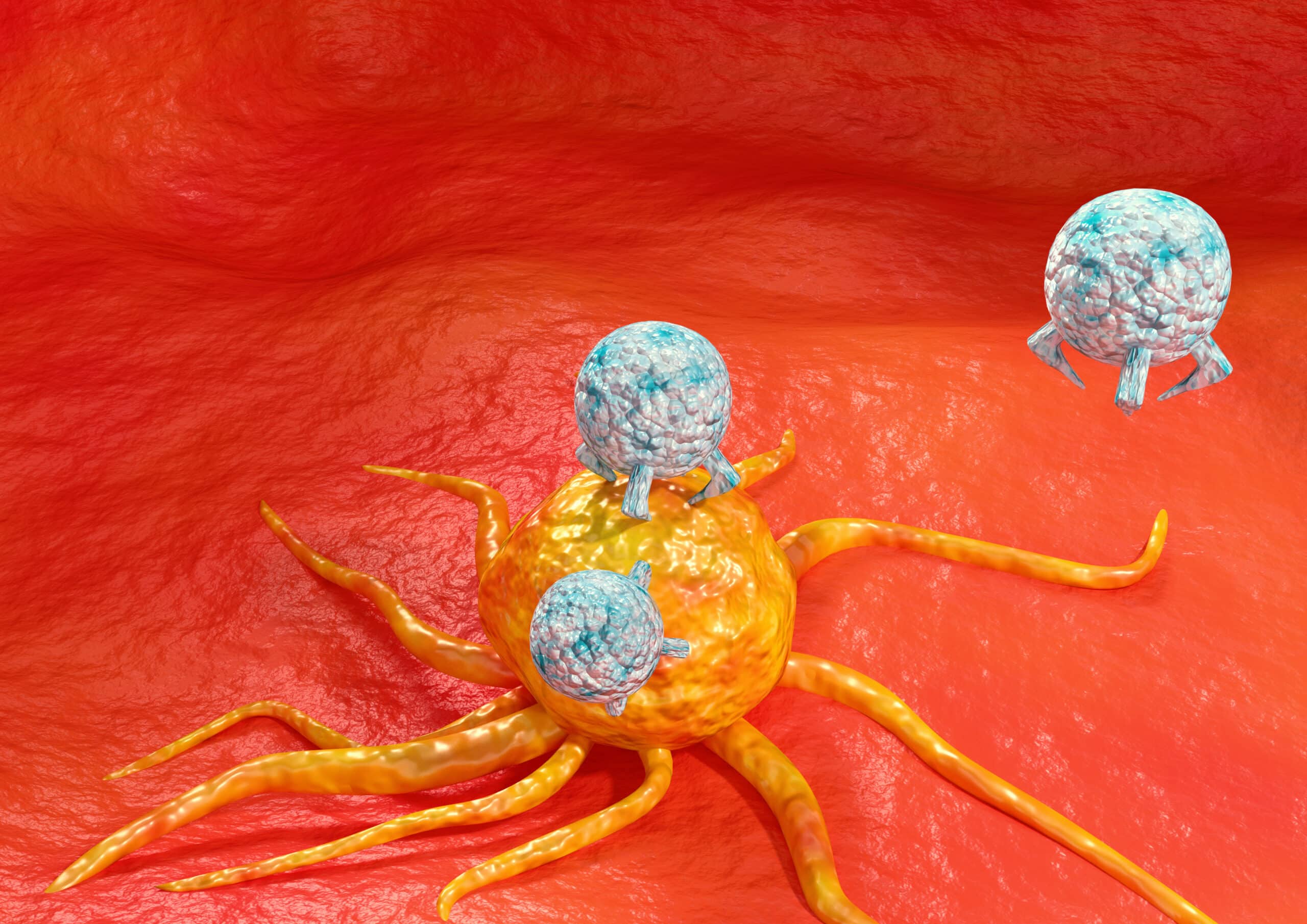

After showing that GD2-targeted CAR T cells could selectively kill retinoblastoma cells grown in the laboratory, the UNC team tested the therapy in mouse models of retinoblastoma.

Because CAR T-cell therapies typically are “one-shot treatments” delivered via the circulation, Dr. Savoldo explained, it can be difficult for the T cells to reach some tumors as well to be “turned on,” or activated, by those tumors they do find. Retinoblastoma is a case in point.

As Drs. Nellan and Fry explained, the eyes are “immunologically privileged” organs—that is, the immune system response in and around the eyes is naturally dampened because of the collateral damage it can cause (e.g., inflammation).

So rather than infusing the T-cell therapy into the mice, they injected it directly into the eye tumors. Although the treatment shrank tumors, it did so only partially, and they quickly regrew.

Other studies have found that a type of immune-stimulating protein, a cytokine known as IL-15, could help CAR T cells stay alive for longer periods, Dr. Savoldo explained. So, similar to what they’d already done with their GD2 CAR T-cell therapy for neuroblastoma, the research team re-engineered their CAR T cells to also produce IL-15.

The enhancement worked. The therapy destroyed the tumors and prevented them from returning for an extended period in more than half of the treated mice.

Finally, in an effort to further ramp up the treatment’s effectiveness, the team turned to hydrogels, gelatinous structures composed of water and other biodegradable compounds.

The study’s other lead investigator, Zongchao Han, M.D., Ph.D., has been testing hydrogels as delivery vehicles for therapies for other eye-related disorders, including diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration. Other researchers have also investigated treating retinoblastoma with chemotherapy drugs loaded in hydrogels.

Packaging the CAR T cells in hydrogels, the research team believed, could allow for a gradual release of their contents in the eye, extending the time the treatment is able to work. It could also help limit the distribution of IL-15 beyond the tumor, reducing the risk of side effects that have been linked to IL-15 in other human studies.

Experiments in retinoblastoma cells and mouse models of the cancer seemed to validate those expectations.

For example, when the researchers injected hydrogel-encapsulated GD2/IL-15 CAR T cells into tumors in the mice, they were completely eliminated in all of the mice and did not return for the duration of the study. Additional experiments found that the CAR T cells remained around the tumor site, which is important to help prevent the tumor from recurring.

In addition, the therapy “also improved structural recovery of the retina” in the mice, they reported. Additional analyses showed that untreated mice had significantly impaired retinal function, whereas mice that received the hydrogel-packaged treatment appeared to have good retinal function.

What’s Next?

Drs. Nellan and Fry called the results from the mouse studies “promising,” particularly because of the limited damage to the retina and the finding “that this treatment results in improved [retinal] function.”

Dr. Gonzalez agreed that hydrogel-packaged CAR T cells are promising and should continue to be developed. The treatment’s impact on the retina will need further scrutiny, he added, because the mouse model used in the study doesn’t replicate the retinal damage that is often present in children by the time they are diagnosed with this cancer. “At that point, they often already have some dysfunction of the retina,” he said.

CAR T cells are not the only new approach to retinoblastoma treatment being studied. Researchers in Spain, for example, have developed a cancer-targeting, or oncolytic, virus that shrank tumors in animal models of retinoblastoma and has been tested in a handful of children with the disease.

A challenge for any new treatment approach, Dr. Gonzalez noted, will be the fact that retinoblastoma is rare, so clinical studies are difficult to conduct. In addition, despite their shortcomings, the current treatments are effective and relatively safe.

Testing these new therapies in combination with standard treatments may be one inroad into clinical trials. “I think it will be interesting to see how they can be incorporated into existing treatments, at least in the beginning,” he said.

The UNC team is in discussions about possible clinical trials, including collaborating with other centers involved in CAR T-cell therapy research, Dr. Savoldo explained. “We’re definitely thinking of the best way to move ahead with trials,” she said.