Antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections are a growing health threat worldwide. One such bacterium, called methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), can cause dangerous or even deadly skin infections.

MRSA spreads easily in healthcare facilities and in the community. Severe MRSA infections now affect hundreds of thousands each year in the U.S. Researchers are looking for new ways to fight MRSA and other bacteria without antibiotics.

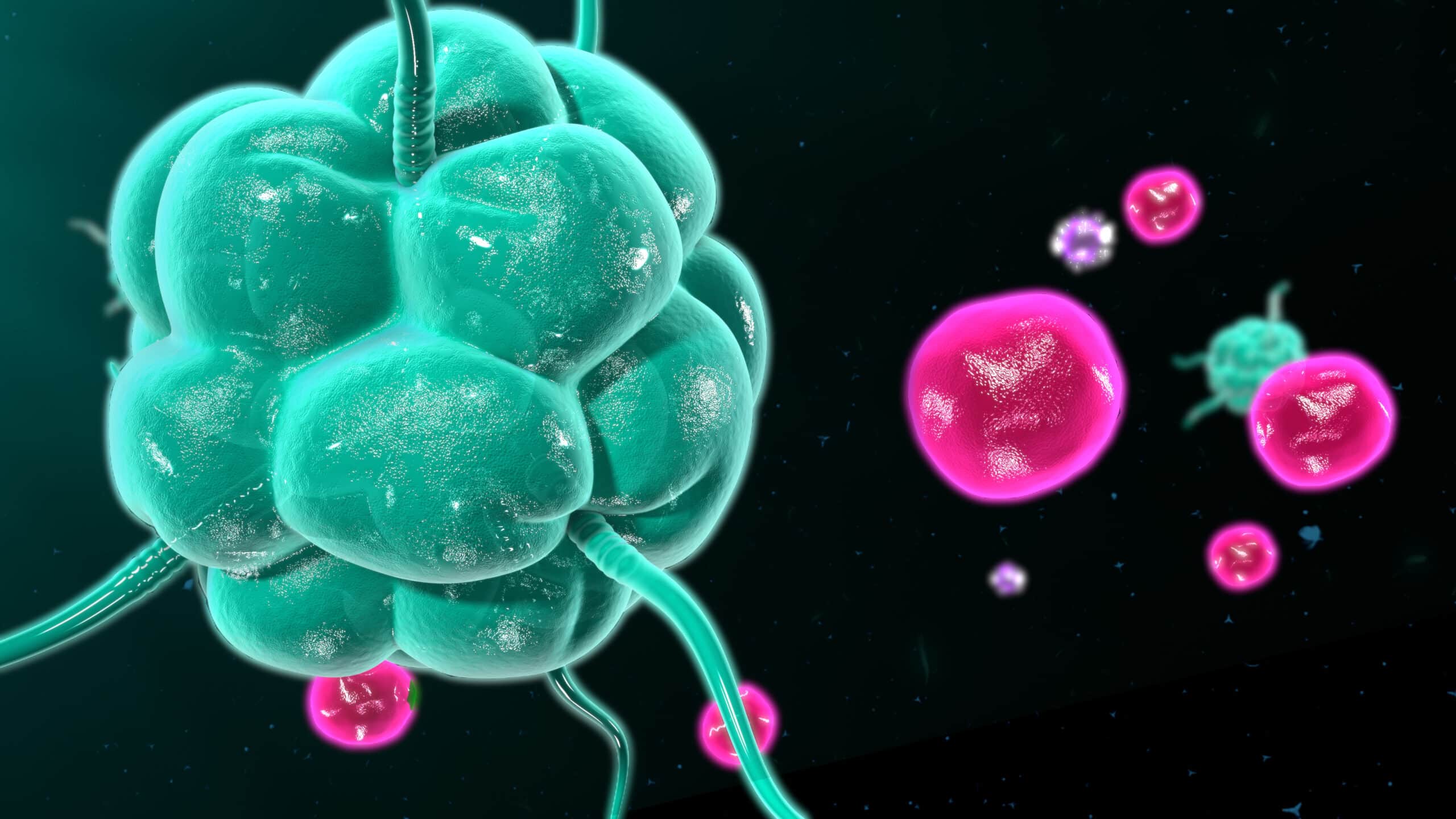

A research team led by Dr. Lloyd Miller, formerly with Johns Hopkins University and now at Janssen Research and Development, have been testing ways to boost the natural ability of the immune system to clear infections. In a new study, they tested a drug called Q-VD-OPH in mice with MRSA skin infections. Q-VD-OPH is a type of drug called a pan-caspase inhibitor. Such drugs block molecules in the body called caspases. These play an important role in telling cells when to enter the body’s natural recycling process and die.

The study was funded by NIH’s National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Results were published on July 7, 2021, in Science Translational Medicine.

Mice with skin wounds caused by MRSA given Q-VD-OPH had substantial reductions in wound size and in the number of bacteria in their wounds compared with untreated mice.

Skin samples from the mice given the drug also had more bacteria-fighting immune cells than samples taken from untreated mice. Further experiments showed that Q-VD-OPH prevented neutrophils and monocytes from dying, leaving more of these immune cells available to fight infection. However, the drug increased the death of macrophages, another type of immune cell.

Q-VD-OPH also reduced wound size and the number of bacteria in wounds caused by two other pathogens: Streptococcus pyogenes and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Both of these bacteria can cause serious illness in people. In the experiments with P. aeruginosa, 40% of the untreated mice died from infection that spread elsewhere in the body, but none of the mice given Q-VD-OPH did.

In further experiments, the team found that an immune system protein called tumor necrosis factor, or TNF, was required for Q-VD-OPH to have its effects. Neutrophils and monocytes in the infected skin produced the protein. So did dying macrophages. Additional work identified specific caspases affected by Q-VD-OPH. This information could potentially allow for the development of more targeted immunotherapies.

In explaining the effects of Q-VD-OPH on the immune system, Miller says, “It’s like a fire department where older firetrucks are kept operating to help put out blazes, when otherwise, they would have been taken out of service.”

The findings suggest that caspase inhibition could be a valuable alternative to antibiotics for treating certain infections. Further study is needed before the approach could be tested in people.