The study which seemed to have sparked the coconut oil health fad was recently reviewed by Marketplace, and it appears as if the author of that study isn’t buying into the coconut oil health trend:

“It’s unfortunate that coconut oil has been given this health halo,” said Marie-Pierre St-Onge, whose research is often used to make coconut oil health claims. “Especially since we know that saturated fats increase cholesterol concentrations, which increases your risk of cardiovascular disease.”

The study was conducted in 2003 when the team was searching for solutions to the obesity epidemic which found use of medium chain triglyceride saturated fats may help people who are overweight drop unwanted pounds.

Chemical structure of MCTs are slightly different and shorter than common long chain saturated fatty acids, and some of the saturated fat in coconut oil is considered to be medium chain; after this study was published coconut oil began to be promoted as a health food that may help with weight loss, despite St-Onge saying that only 15% of coconut oil should be considered as MCT.

“I think companies should be responsible in their communication to the public and making sure that a research that’s been done is being translated accurately,” she said and adds “I would not consume it on a regular basis in large quantities.”

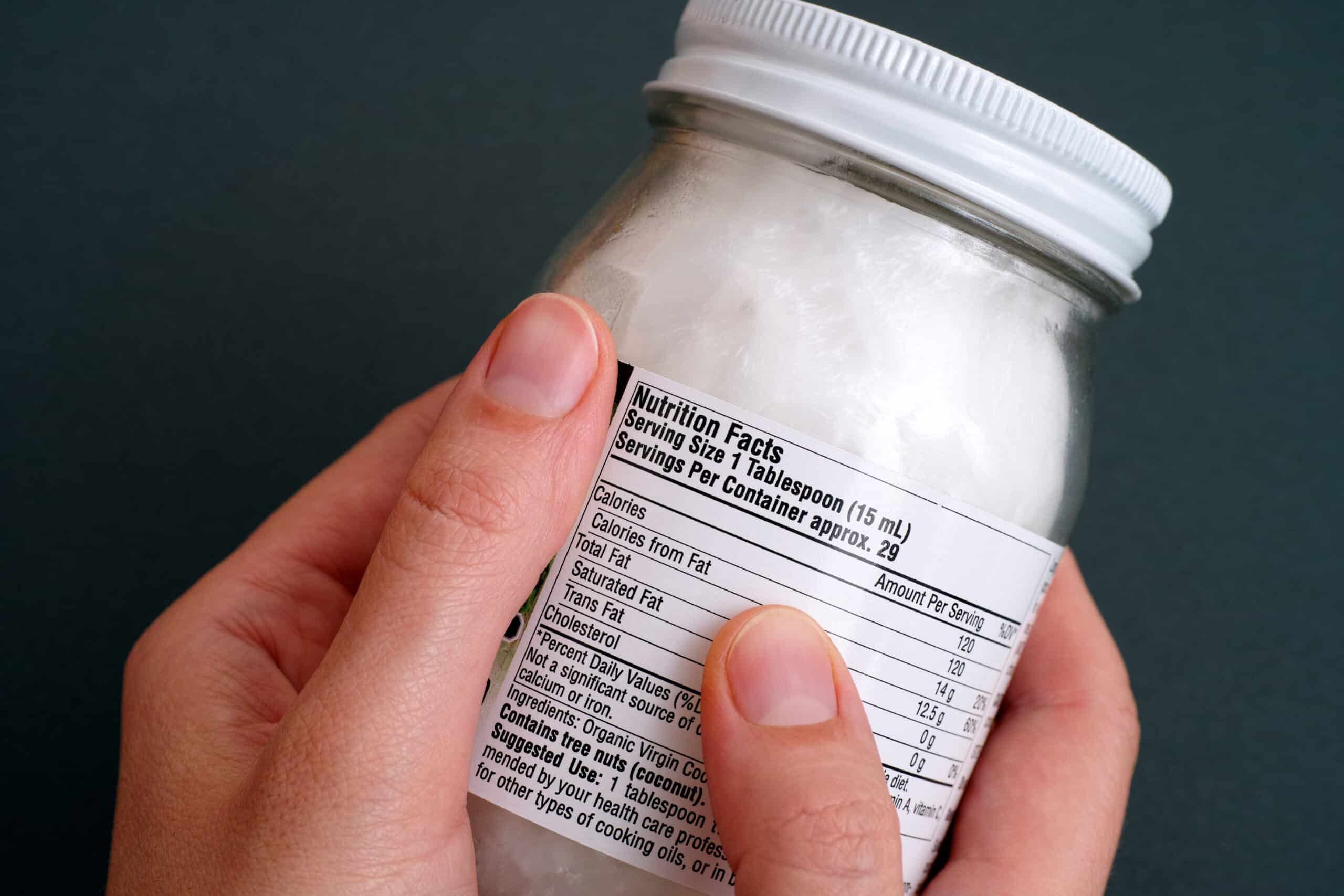

Coconut oil is often recommended as a one for one substitute for butter and oil in recipes and as a trendy keto addition to coffee in the morning, even though just 1 spoonful represents 70% of Health Canada’s daily recommended limit of saturated fat which has been long associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease backed by decades worth of studies that influence public health policies around the globe.

This research is not the only work used to back up the halo that adorns coconut oil: The Coconut Coalition of the Americas industry group represents some of the major brands of coconut oil suggests that people should consider other studies that have concluded that saturated fat doesn’t affect cardiovascular risk such as the PURE study that didn’t actually study coconut oil but concluded that those eating more saturated fat had better health outcomes than those who ate less.

The PURE study was published in the Lancet, but experts still disagree on how the results should be interpreted, such as the conclusions being criticized by Harvard School of Public Health for using subjects from developing countries with diets that were particularly high in refined carbs and were indicative of a poverty diet. A review of the study in the American Journal of Medicine also made note of this saying “adequate nourishment in the diet was likely the reason for less death” and that the results “may reflect a need for any type of fat in the diet to treat nutritional deficiencies.”

Nutritional studies can have conclusions which can be controversial sometimes since they are largely observational, thus they can be more subjective. “You can pull all the research together and look for consistency,” said Dr. Michael Greger, an American physician, author and public speaker who founded NutritionFacts.org to help consumers make sense of nutrition studies. Science is self correcting with new discoveries, advances and changes, within it no field of study is more endlessly self correcting than the field of dietary health.

Typical pharmaceutical clinical trials use the gold standard of randomized double blind placebo controlled studies, but this becomes tricky to do with nutrition. “It’s easy to randomize people to 10 weeks of eating in a certain way. But they can’t randomize people eating for decades in a certain way,” he said. “Some of these chronic diseases take decades to develop.”

Most science shows that high intake of saturated fat can raise LDL cholesterol levels in the blood which is associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease. In Canada 1 in 2 people eat saturated fat in quantities that go beyond the recommended daily limit of 20 grams which includes trans fats.

Health Canada recommends that along with trans fats, saturated fat intake should be kept as low as possible, and suggests replacing it with mono-unsaturated fats or ploy-unsaturated fats which can be found in olive oils.

Products are not always obvious as to which ones are high in saturated fats, especially if they are being marketed as a health food. Costco in America was involved in a class action lawsuit over the Kirkland brand of coconut oil: “Costco misleadingly labels and markets its Kirkland Coconut Oil as both inherently healthy, and a healthy alternative to butter and other oils, despite the fact that it is actually inherently unhealthy and a less healthy alternative,” read the statement of claim.

The lawsuit was settled with an award of $775,000 going to the plaintiffs and an agreement that the terms “health” “healthful” or any other derivative of the term “healthy” be used on any of the company’s oil labels. Costco agreed to the changes but in a response said that any actions taken to carry out the agreement should not be taken as an admission of the labeling being misleading; Kirkland coconut oil sold in Canada doesn’t carry any health claims on labeling.

Recently the American Heart Association published a public health advisory warning about the risks of consuming diets that are high in saturated fats, which includes coconut oil, and the associated cardiovascular risk.

Canada may be taking this one step further to curb misinformation to help people make healthier choices as Health Canada is proposing putting front of label advisories on all foods that are especially high in sugar, salt, or saturated fats; think of warning symbols put on dangerous compounds.

In a statement, Health Canada said according to the proposed regulations, “coconut oil would be required to carry a ‘high in saturated fat’ symbol.” Currently the proposed regulations are being reviewed after extensive consultations over recent years, and they would be part of the Healthy Eating Strategy that has revamped Canada’s Food Guide early into 2019.

Until the proposed regulations are approved and implemented it remains up to the consumer to take the time to read ingredient/nutrition labels to see if their health claims add up, and to listen/read all the flashy hype, marketing, clickbait, and news headlines with a grain of salt; meaning people need to read things and decide/think for themselves and not follow trends and do as others do or say because the brain is too beautiful to waste. As always, moderation is the key, especially in conjunction with exercise and/or an active lifestyle.

“If you actually look at the peer-reviewed medical literature going back decades, it’s really a consensus around the core elements of healthy eating. But they’re still able to get clickbait papers published,” said Greger. “It sells a lot of magazines, but it sells the public short.”