The study, published in the journal Blood, was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), part of the National Institutes of Health.

“These study findings suggest that measuring DNA of mitochondrial origin could help us better understand its role in pain crises, destruction of red blood cells, and other inflammatory events in sickle cell disease,” said Swee Lay Thein, M.B., D.Sc., chief of the Sickle Cell Branch at NHLBI. “It could also serve as a marker of disease progression and a way to measure the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions.”

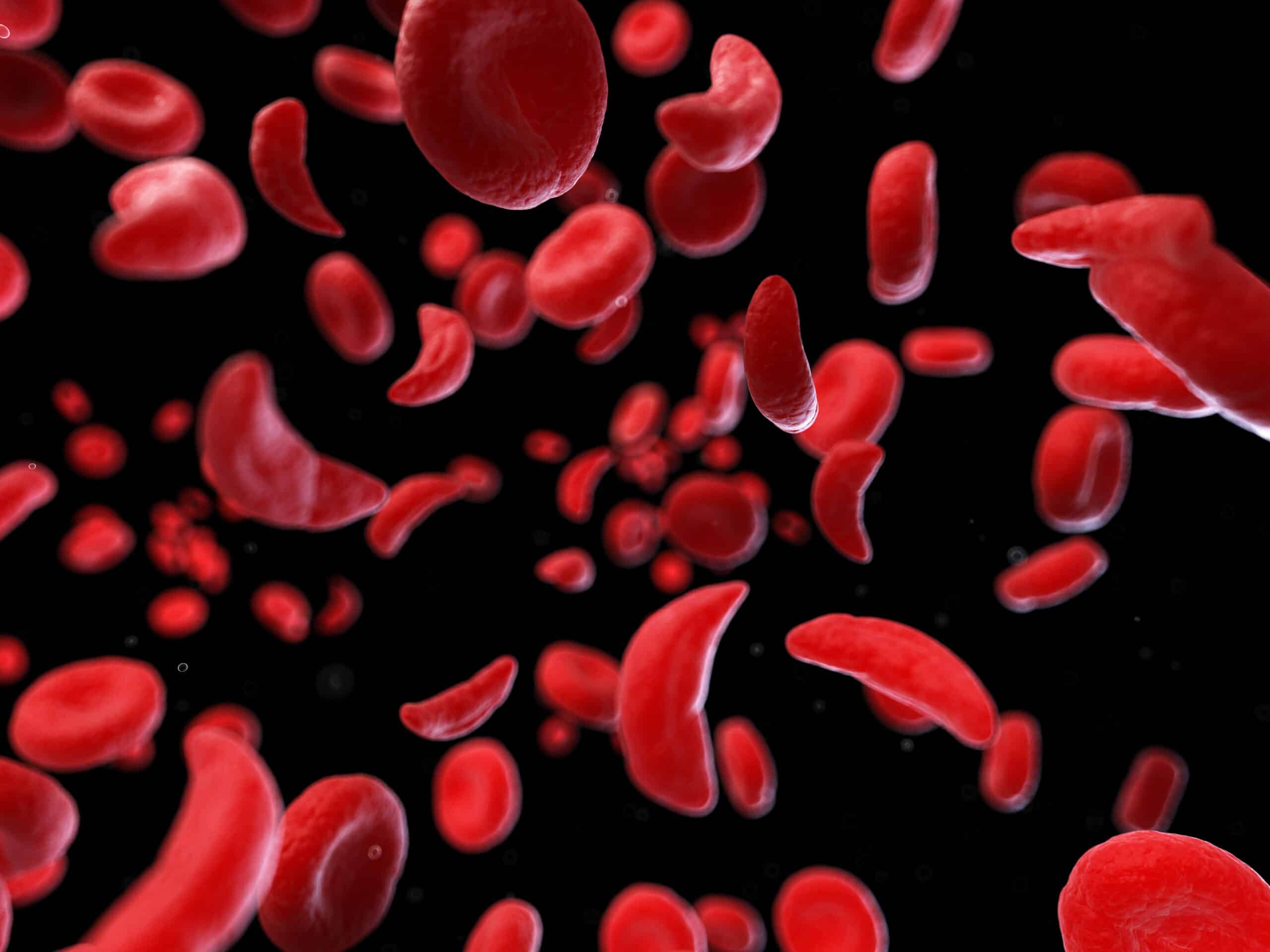

Normally a red blood cell gets rid of its mitochondria when it matures, because the energy from mitochondria is not needed to carry out the red blood cell’s function of delivering oxygen throughout the body. However, Thein and her team showed that red blood cells from people with sickle cell anemia – the most common and often most severe type of sickle cell disease – abnormally retain the mitochondria, which can lead to a buildup of highly reactive chemical molecules that stresses the cells.

This condition, researchers found, allows damaged mitochondrial DNA to enter circulation with too few of the small molecules, called methyl groups, that typically attach to the DNA to help the cells function. This abnormal amount of molecules on the mitochondrial DNA, in turn, stimulates inflammation, a hallmark of sickle cell disease.

To do the study, Thein and her staff scientist, Laxminath Tumburu, Ph.D., the study’s main author, analyzed the complete set of DNA extracted from the blood plasma of 34 people with sickle cell anemia, as well as the blood plasma from eight healthy volunteers.

“We were intrigued when we found higher levels of free-floating mitochondrial DNA in the plasma of the patients with sickle cell disease,” Thein said. “These were shorter and more fragmented than free-floating nuclear DNA fragments, which are also known to drift in the patient’s blood.”

The free-floating mitochondrial DNA from patients with sickle cell disease had fewer methyl groups than were found in the blood plasma of the healthy volunteers. As intriguing: the free-floating mitochondrial DNA from seven of those patients had even less of these methyl groups when the patients were having a pain crisis, compared to when they were not.

To examine why this was the case, the researchers looked at how the blood plasma containing high levels of free-floating mitochondrial DNA triggers a specific inflammatory process. Neutrophils are part of the immune system and they form structures called neutrophil extracellular traps, or NETs that are crucial components of the immune response and are typically protective in bacterial or viral infections.

But a negative consequence of these NETs is inflammation that is detrimental and often continual, even in the absence of infection. Knowing this, Thein and her team were able to block the formation of NETs by treating neutrophils with a small molecule inhibitor.

With this improved understanding of the components that contribute to the sickle cell disease process, the researchers said they now want to pursue preclinical testing of drugs that target mitochondrial DNA and the inflammatory process it stimulates.

Image: Scanning electron microscopy image of mitochondrial bundles in several sickle cell red blood cells, showing evidence that circulating red blood cells from people with sickle cell disease abnormally retain mitochondria. Image Credit: Swee Lay Thein, NHLBI