Dozens of hospitals have recently started offering parents the ability to sequence their newborn’s genome to help diagnose life threatening conditions shortly after birth. Several companies are also now marketing direct to consumer tests to parents, and this prenatal and newborn genetic sequencing is expected to develop into an $11.2 billion industry by 2027, which is an increase from the 2018 market of $4 billion.

Genetic testing of newborns may help to diagnose a life threatening childhood onset disease, and in urgent cases it may increase the number of genetic conditions all babies are screened for at birth which may enable earlier diagnosis, intervention, and treatment. The process may inform parents of conditions they may pass onto future children or even their own risk of adult onset disease. Such testing may detect disease in a magnitude greater than the current tests which all babies born in American undergo at birth or confirm results from these tests.

35 genetic diseases can be detected in newborn blood testing, these tests look for parts of proteins or other molecules linked to treatable gene associated ailments. 193 illnesses can now be identified through DNA using commercial genetic testing panels for newborns. 1,514 genes each being responsible for a different childhood disease were identified in the BabySeq. Study which looked for DNA tied to treatable illnesses, genes that affect responses to drugs, and for genes that don’t affect the baby but can be passed on and cause disease in future generations.

But still some argue that such testing has the potential to do more harm than good such as missing diseases that heel stick testing detects, and they can produce false positives and cause anxiety leading to unneeded additional testing. Such testing of newborn children’s DNA also brings up questions and concers about issues of consent, privacy, security, and the prospect of genetic discrimination.

While many question if the technology is sophisticated enough to be truly useful for babies and of society is ready for such information, for better or worse newborn genetic testing is here, and likely to become more common, questionable results or not. There are about 14,000 known genetic diseases in humans, heel stick tests look for a fraction of these disease which is part of the reason that genetic testing holds appeal. Standard testing can also take weeks or longer whereas rapid sequencing methods and software can get this done as quickly as a day or two, and for sick babies it can mean the difference between life, severe disability, or death.

The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Human Genome Research Institute launched the NSIGHT program to explore the risks/benefits of DNA screening newborns. One of the 4 projects funded by the program explored the use of rapid whole genome sequencing in sick newborns suspected of having a genetic disease; over 1,100 babies were sequenced 1 in 3 received diagnosis identifying an illness and 1 in 4 had their treatments changed as a result. In these cases sequencing likely saved lives, and probably reduced the amount of diagnostic testing the children would had to have endured.

Another of the NSIGHT projects is investigating whether sequencing could be used in a clinical setting to screen newborns with no obvious signs of disease. A list of 1,500 genes associated with diseases that begin in childhood or adolescence was developed; the group reported results from 159 newborns in January 2019 finding that 94% of the healthy group were at the risk of developing childhood onset disease not known from their medical is family history of which 88% were carriers for recessive diseases.

BabySeq was not intended to be a feasible addition to newborn screening, and although the main initial focus of BabySeq was on childhood onset disorders one baby was found to carry a variant of the BRCA2 gene which is highly associated with a high risk for certain cancers. When the researchers asked the parents if they wanted to be informed on their baby’s risk of adult onset disorders they declined to receive the information, opting to let their child get tested at an older age if he wanted to be tested, feeling it should be the child’s decision.

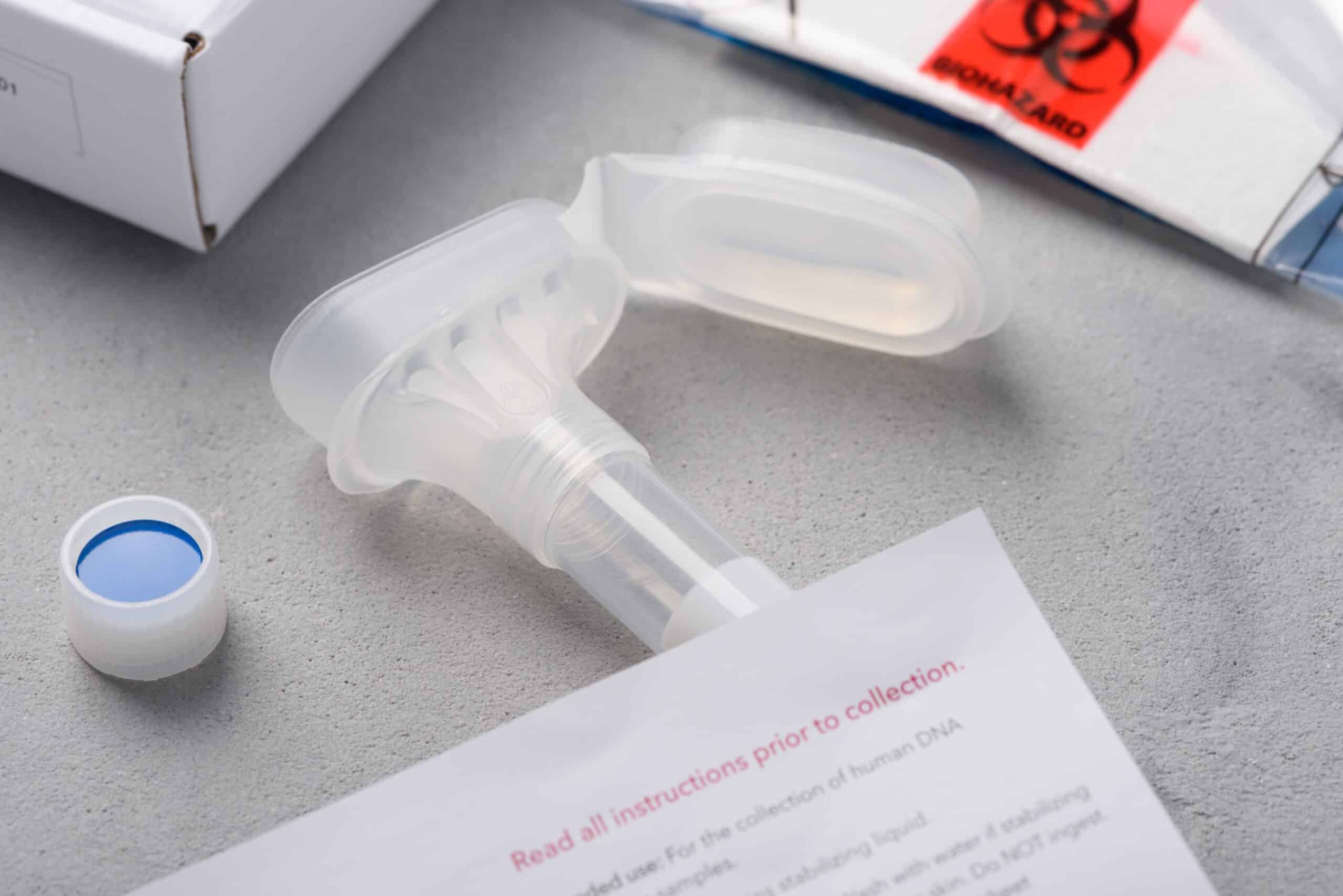

Regardless of the US FDA pressuring companies not to make such information available, such testing is no longer confined to clinical practice as several companies are now offering direct to consumer DNA testing for newborns. Some of these at direct to consumer at home kits claim to have an accuracy of 88-99%, even though the FDA has not reviewed their tests and they may not be backed up by clinical evidence.

One of the concerns is the false positives, which is a known issue. However, it is worth noting that when used in combination with standard screening it has been found to be helpful. Genetic testing may cause unnecessary anxiety over diseases that may appear later in life or not even show up at all. Most people don’t understand how to interpret what the results mean and how to proceed, adding to the burden of counselors and doctors to sort out.

That brings us to questions about the safety and privacy of the child’s information, where it is being stored, who has access to it, and what happens if this information becomes public. GINA prohibits such discrimination, but it does not cover insurance for long term cares, life or disabilty, it does not apply to those insured or employed by the military’s system, and it does not aply to small businesses with less than 15 employees.

Cost is another factor as clinical sequencing ranges from $500-1,500. Those that can’t afford health insurance will likely not able to afford this either, or the follow up with specialists that genetic testing can lead to and it would add to the burden of the healthcare system. If sequencing turns out to save money insurance companies may eventually cover these tests, but there is no guarantee.

Majority of sequencing thus far has been done in babies from families that are financially well off and white, which raises concerns that such approaches may become the province of those who are considered to be privileged and the racial homogeneity will likely skew most results: diseases more prevalent in Caucasian would be overrepresented in test panels while those in racial minorities would be underrepresented.

Despite these concerns and others it appears as if the era of newborn sequencing has begun, and it will likely become more common as prices decrease and results become more accurate/useful. Keep in mind that the risk/benefits of sequencing should be weighed on an individual basis such as a very sick newborn being tested in hospital is a completely different case than parents worried about their healthy children making them more susceptible to direct to consumer at home marketing.

Barbara Koenig, professor of medical anthropology and bioethics at U.C.S.F. and one of the NSIGHT report’s co-authors, stresses that sequencing, while promising, is not yet mature enough to be routinely used to screen healthy children. “This is not a technology that’s ready for prime time for use in healthy infants.” The NSIGHT report concluded such sequencing has benefits in diagnosing sick children, but using genome sequencing as a replacement for newborn screening is “at best premature,” and suggest at home direct to consumer sequencing should not be used for diagnosis or screening purposes.