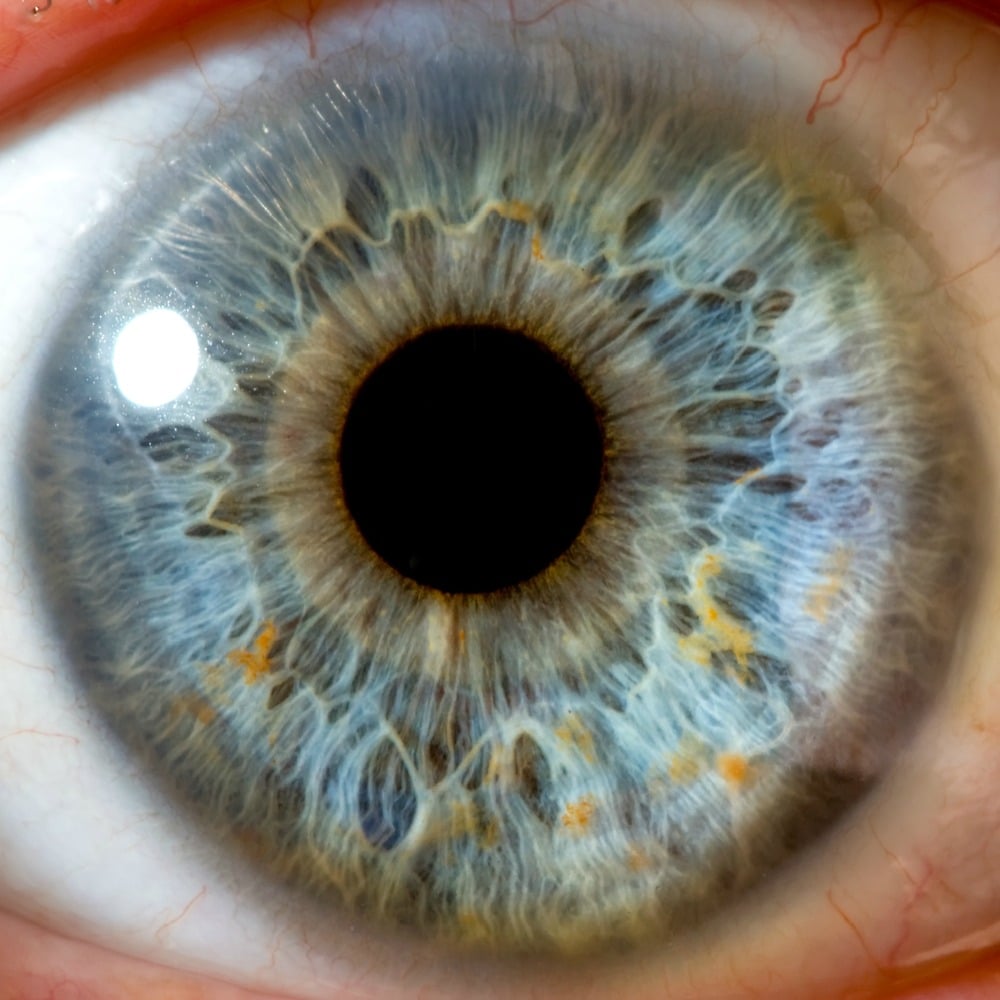

Bugs in the eyes sound like a premise for a horror flick yet such a phenomenon might actually be beneficial. A new study shows microbes living on human eyes are important for healthy immune responses. These responses protect the eyes against infection. The findings were made in a recent study conducted by researchers at the National Eye Institute (NEI). The results were published in the journal Immunity.

Findings

The researchers determined an ocular microbiome trains the developing immune system to combat pathogens. This is the first sign that bacterium lives on human eyes across an extended period of time. This study examines the long-standing question as to whether ocular microbiomes exist. The medical community long-believed the ocular surface was sterile due to the presence of the lysozyme enzyme. This enzyme eliminates bacteria along with antimicrobial peptides and other factors that remove microbes from the eye. These microbes can land on the eye’s surface from the air or even one’s fingers.

About the Study

Caspi research fellow, Anthony St. Leger Ph.D., cultured bacteria stemming from mouse conjunctiva. This is the membrane along the eyelids. He identified numerous species of Staphylococci that are often found on the skin. He also found Corynebacterium mastitidis, commonly referred to as C. mast. However, it was not clear whether such microbes had recently arrived along the surface of the eye or if they were on their way to being destroyed. Nor was Dr. St. Leger certain as to whether the microbes lived along the surface of the eye for a lengthy period of time.

Dr. St. Leger’s team determined C. mast cultured with immune cells derived from conjunctiva spurred the generation of interleukin (IL)-17. This is a signaling protein necessary for the host’s defense. The researchers determined IL-17 was generated through gamma delta T cells. This is a type of immune cell within mucosal issues. IL-17 attracted neutrophils. These are the most common type of white blood cells. They were attracted to the conjunctiva and caused the release of anti-microbial proteins in the tears. The research team is currently studying the distinct features that allow C. mast to be resistant to the immune response it provides and allows it to exist within the eye.

Dr. St. Leger created two control groups to figure out whether the microbe played a part in the immune response. The groups were as follows: one with C. mast and one treated with an antibiotic designed to destroy C. mast along with additional ocular bacteria. They were challenged with the fungus known as Candida albicans. The mice provided with antibiotics had a decreased immune response within their conjunctiva. They proved incapable of eliminating C. albicans, causing a massive ocular infection. The control mice with regular C. mast proved capable of warding off the fungus.

Interesting Observations

Dr. St. Leger observed mice from NIH had C. mast along their eyes. The mice sourced from the Jackson Laboratory did not have C. mast along their eyes. This distinction let the research team determine if C. mast was a legitimate resident microbe or a transient-style microbe. They were also empowered to determine if it was possible to culture the microbe from animals’ eyes in ensuing weeks. The researchers even determined if the microbe could be transmitted among cagemates.

Mice from the Jackson Laboratory inoculated with C. mast produced conjunctival gamma delta T cells that generated IL-17. The research team is unsure as to what allows C. mast to become established within the eye while other forms of bacteria do not colonize. C. mast can be spread from mother to offspring yet not between cage-mates.